Dhamaka’s menu is a holistic portrait of Indian food from the underrepresented parts of the country. Photo Courtesy: Adam Friedlander / Dhamaka

Restaurateur Roni Mazumdar and chef and partner Chintan Pandya’s smash hit culinary venture brings rustic Indian fare to the U.S. cosmopolitan dining scene.

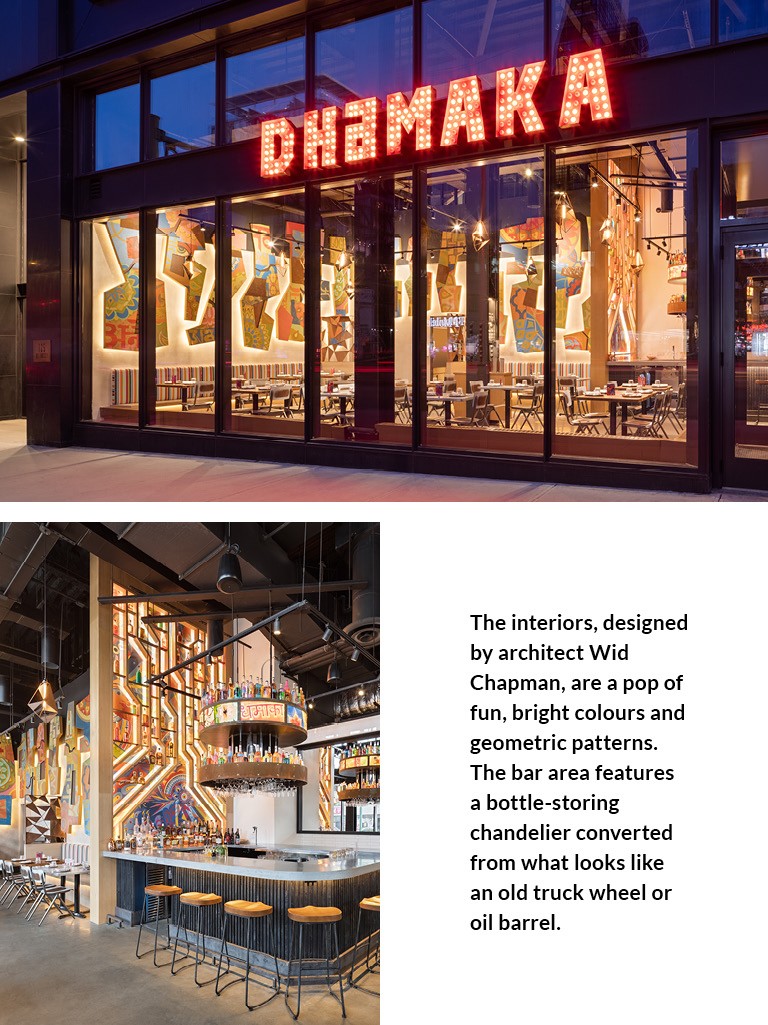

February 14, 2021 saw restaurants in New York unfurl the carpet to diners as indoor seating became a reality once again after a hiatus. It was also the day restaurateur Roni Mazumdar and chef and partner Chintan Pandya of Unapologetic Foods launched Dhamaka in Essex Market on the Lower East Side. The strictly dine in-only venture etched a permanent spot for impenitent Indian food on the city’s culinary map and became a frontrunner of how few in the service industry persevered in the pandemic.

In no time, reservations to secure a table at the venue started filling up a month in advance from across the U.S. It isn’t difficult to comprehend why. The restaurant plates regional specialities such as doh khleh from Meghalaya, Champaran meat from Bihar and chenna poda from Odisha, thereby venturing into a territory that most Indian restaurants wouldn’t dare foray into. A move as brazen could either be fatal or truly rewarding. Fortunately, the odds were in Dhamaka’s favour.

While most restaurateurs tend to fixate on the interiors, Roni and Chintan stayed focussed on the ingredients. Their lamb comes from Denver, their mutton from Arizona, and their rabbit from a farm in Upstate New York. But their glassware? From Ikea. Their not-so-secret ingredient, however, is the freshness. Most items on Dhamaka’s main course menu are made to order and get cooked and served in the same vessel as they would be in a typical Indian household—in clay pots and cast iron. “We really wanted to tell the story of Indian food holistically,” Roni reveals to me over a phone call in late 2021. And just like that, the line between home cooking and restaurant food seems to blur.

Their gastronomic journey is a very personal one and the menu is a culmination of food from underrepresented parts of the country. All the accolades—topping the ranks of New York Times’s 10 new restaurants in New York and Esquire’s 40 new restaurants in America in 2021 amongst others—are just cherries on top. Edited excerpt from an interview with the co-founders:

What is it that you were trying to do with Dhamaka that had not been done before with Indian food in New York?

Chintan: Our vision has been focussed on bringing a new perspective to Indian food and not just categorising it into five odd dishes that include chicken tikka masala and saag paneer. While I was working in India, I travelled a fair bit. I wrote down a lot of recipes, but didn’t imagine using any of them in a restaurant setting. When I was dining at home one day, it struck me that Indian restaurants lack freshness because everything is precooked.

Roni: If you think of Indian food and what it has become, it is an idea of either Punjabi food or Mughlai food and that’s essentially what has gone across the world. Southern India makes an appearance here and there in the form of dosa and a few different dishes. We haven’t explored the beauty and regionality of Indian cooking and that’s the focus of our group. We’re creating restaurants that highlight what our food is actually like and what we eat at home. We’re bringing worlds together.

You say you travelled extensively across India before you imagined a menu for Dhamaka. Can you elaborate?

Chintan: We have a dish called Champaran Meat, which is very famous from the eponymous region in Bihar. Then there’s chenna poda from Odisha and from Meghalaya, there’s a pork head salad called doh khleh.

You have other restaurants in the U.S. How did that journey set the tone for what you wanted to do with Dhamaka?

Chintan: I’m a Gujarati who grew up in Mumbai and I like chatpata food. And Adda Indian Canteen is a representation of that. We have vada pav and pav bhaji on the menu. Rahi (now a South Indian restaurant called Semma) was actually the highest revenue-making restaurant for us. But when Unapologetic Foods started to grow as a company, we decided to focus on the regional aspects of Indian food. Chef Vijaya Kumar is from a small village in Tamil Nadu. We’ve had people from Tamil Nadu cry at Semma because they couldn’t find such food elsewhere.

Roni: We’re serving snails because the chef grew up picking them up with his grandma from rice paddies. When we think of South India, we think of the Hyderabadi biryani. Here, we’re serving a local variation of the biryani. He used to go hunting with his grandfather. That’s why we have venison on the menu. There’s an oxtail recipe from a family that made it for him. When you start looking at the various angles, you start to understand that Indian food isn’t a monolithic structure. It’s so incredibly diverse. At Dhamaka, Chintan wanted to bring to the forefront the regions that are rarely talked about and the dishes that are overlooked. We call it “the forgotten side of India.” It’s so telling because in many ways, our own cuisine is slowly being forgotten when we are all obsessed with the cuisine of the West that is picking up. We seem to know more about the next pizza and burger trend than the food from Meghalaya or Bihar. India shouldn’t feel the same because it’s not the same.

What sort of an Indian traveller drops by Dhamaka? Can you cite any interesting exchanges about Indian food with them?

Chintan: We have a lot of people coming from across the country. We have regulars from California, Texas and Pennsylvania. I’m from Mumbai, but lived in Delhi for two years. We actually have people from Delhi who have lived in the U.S. for a few years and they say that the paneer at Dhamaka is not only on par with the one they’d have back home, but it might just be better.

Roni: We’ve had people show up from Champaran, Odisha and Meghalaya and tell us that for the first time in their life, they have felt included in Indian food conversations and they finally have an identity and a voice that’s been heard. They have something to contribute to and to be proud of. That means the world to me.

Which are some of your marquee dishes? What’s the inspiration for the menu?

Chintan: There’s the Rajasthani kharghosh. We only take one order of the dish every night since the rabbit takes up to 48 hours to cook. And it’s priced at $225 with taxes. We source the rabbit, which typically weighs around 3.5 lbs and is one of the biggest of its kind available in the market, from a farm in Upstate New York.

Roni: You know, our Champaran meat is not only made in a clay pot but also gets served that way, and our chicken pulao in a pressure cooker. Our paneer methi is made to order. There are two sides to this: the non-Indians are excited about the diversity and something new. The Indians are even more excited for the same reasons. We realise that most of us end up exploring the food of the region we grew up in. The rest of it is the biryani, butter chicken and naan. That’s become quintessential restaurant food. Today you’re also going to find Indo-Chinese. So when someone from Tamil Nadu shows up and says that they’d never known that snails exist in their cuisine, or when someone from Rajasthan shows up and says they’ve never had a kharghosh in their lifetime—these are barrier-breaking conversations. It’s all so brand new, but at the same time so rural and quintessential to be flavour profiles of our own childhood.

What were your defining Indian food memories growing up?

Roni: I grew up in a Bengali household. For me it’s luchi and kosha mangsho. This is something I’d kill for. There’s also bhapa chingri. There was a specific chicken pakora that I used to have from the outskirts of Bengal. Our latest venture—a fried chicken concept called Rowdy Rooster in New York’s East Village—profiles the Indian spiced fried chicken.

Chintan: Having grown up in a Gujarati household, I’d only eat vegetarian food at home and everything else outside. My fondest food memories are of a dish called dal dhokli. That was a weekly Sunday fixture. My grandmother’s version tasted like ravioli stuffed with jaggery. So much of the food I ate was also seasonal. In winters, we made undhiyu and gajar ka halwa twice or thrice a month. Summers were always about aamras and puri. My mom makes phenomenal pav bhaji.

Roni: I just remembered, if you go to Calcutta, there’s a restaurant called Royal that makes insane chaap with a Calcutta version of biryani. I would take that over drugs! (Laughs)

Chintan: I’ve lived in Calcutta and I didn’t like the food there. But there are two things that I’d recommend: one is the Indo-Chinese food in Tangra Chinatown and the other is the chaat at any marwari mithai shop.

In terms of understanding the Indian flavour palate, where does U.S. dining culture currently stand? Have you seen an evolution over the last two-three years?

Roni: I think that we have all been working under this assumption that there needs to be a specific palate to appreciate good food and that’s not true. That theory has been disproved by the advent of what Dhamaka, Semma and Adda are doing. None of the dishes on the menu have been changed. People appreciate exciting flavours. The biggest shift that I’ve seen in the last five years in the U.S. is the openness towards each other’s cultures. And finally, also with the emergence of social media, you’re seeing things that you might have cringed at or not have even seen in the past. I’ll give you a simple example. Macher jhol is a dish I’d never want my mother to cook when my non-Indian friends would come over. Because I would be embarrassed by the horrible smell as though I’d invented it. Fish smells the way it does. But today, we have a rustic, village-style macher jhol on Dhamaka’s menu and it’s one of the bestselling dishes. A lot of it has to do with our own insecurities. Rather than trying to understand someone else’s palate, be true to who you really are and serve the food with authenticity and integrity. And I think people will respond.

Chintan: I think Indian chefs and operators tend to create boundaries around themselves. At least in NYC, everyone wants to experience different cultures and try different cuisines. We’ve seen it grow and that’s not true of just Indian food.

Roni: You have to look at Thai food in this country. Chinese food is so far above. When you look at Mexican food, you start to get an idea of what ethnic food is. And that’s when you start to realise that all these people are being really honest about their cuisine. Why do we feel like we need to project an image of ourselves that fits into someone else’s criteria rather than what it is for us? How many Italian restaurants are going to change the taste of pasta just because an Indian has walked in? None. Then why are we so obsessed and consistently apologetic about our food being a little spicy? It’s not about changing the world around Indian food. It’s about changing ourselves so the rest of the world can see who we really are.

Can you list some of the best Indian food cities in the U.S., where there is a real variety and innovation as far as desi food goes?

Chintan and Roni: Nowhere.

Roni: It’s a blank slate. I’m being dead honest. You talk to any local who understands the U.S. and has spent more than enough time here. I think New York is the only place that’s barely scratching the surface. This is a statistic we always share. You know how many Mexican restaurants there are in this country?

Chintan: An estimated 56,000. There are around 37,000 Chinese restaurants. Can you guess how many Indian restaurants there are? Five thousand. Now think about it: this is a country with a substantial Indian population.

Roni: New York is probably the only one and if you think about other cities, there’s Los Angeles, San Francisco, Miami, Chicago and Washington D.C. I’m not saying there are no good Indian restaurants in the country. But they’re far and few in between and not nearly enough to make a real impact.

And why do you think there are fewer Indian restaurants as compared to their Mexican and Chinese counterparts?

Roni: Most Indians don’t go out to Indian restaurants because they don’t get real Indian flavours. Then you have to look at immigration patterns in this country. Most of the people that came here ended up becoming doctors, engineers, and finance guys. There was nothing exciting about Indian food to any of them. The service industry was seen through a classist lens. That is the fundamental difference between what happened with the Chinese and the Mexican population. Then there was a large number of Punjabis that came in not necessarily with H-1B or educational visas. And they ended up making ends meet by setting up mom-and-pop Indian restaurants. There are only two reasons why someone would open an Indian restaurant: one is to make ends meet and the other is to make a statement. The space in the middle where there’s a sense of purpose has clearly been missing and the soul of our cuisine has been wavering because of it.

Have you noticed any distinct changes in the restaurant business and consumer behaviour in light of the pandemic?

Roni: I think the change has been substantial even pre-pandemic. The pandemic has made consumers appreciate things a little bit more. Restaurants, especially in New York, are a part and parcel of our lives. We took it all for granted. And all that went away at the drop of a hat. Many restaurants that we love closed down. We understood that maybe restaurants are more than just places that serve food; they’re an integral fabric of our society. Now I see a higher rate of excitement about restaurants from people.

Does Priyanka Chopra’s restaurant Sona feel like a healthy competition to Dhamaka?

Chintan: There are only 5,000 Indian restaurants in the country. There is no competition among us. It could have been a consideration had there been at least 25,000 restaurants.

Roni: Just because they happen to be a part of the same cuisine doesn’t mean they have to be compared to each other. You have to think of the philosophy of the food. I cannot think of a single restaurant in the country that’s similar to Dhamaka. We just look at it as a product. Is it unique? Does it have a clear perspective to keep moving forward? I want to see more Indian restaurants. And I think that’s the future.

CHINTAN PANDYA’S RECIPE OF GURDE KAPURE

INGREDIENTS

Gurde Kapure 2 pieces each

Oil 60 ml

Red onions 115 gm

Tomato 115 gm

Stock 250 ml

Ginger garlic paste 30 gm

Green chillies 2 pieces

Cilantro 57 gm

Whole dry red chillies 1

Black cardamom 1

Cloves 2

Cinnamon stick 1⁄2

Red chilli powder 15 gm

Turmeric 15 gm

Lime 1 wedge

Salt to taste

METHOD

Wash and clean the gurde (kidneys) and the kapure (testicles).

Finely chop the onions and tomatoes. Slit the green chillies and chop cilantro.

Mix the powdered spices (red chillies, turmeric and salt) with some water and make a paste. Set aside.

Heat oil in a wok. Add the whole spices (red chillies, cardamom, cinnamon and cloves) to season the oil.

Once the whole spices crackle and the oil is seasoned (you can tell from the fragrance), add ginger-garlic paste and fry until the raw smell goes away.

Add chopped onions and fry until they turn light golden and ensure not to let them brown completely. Stir frequently.

Add finely chopped tomatoes and fry until the paste releases its oil.

Add the paste made with powdered spices and mix well for about a minute.

Now add the gurde kapure and stir fry for a minute, coating it with the masala.

Cover the kadhai with a lid, add the stock and let it cook for about 7–8 minutes on medium heat until the masala thickens and the meat has changed colour.

Once gurde kapure is cooked, adjust the salt, garnish with slit green chillies, chopped cilantro, squeeze in lime and leave it covered on low heat for just about a minute.

Your gurde kapure are ready to be served with pao.

(Disclaimer: The recipe has been adapted for editorial use. All rights reserved.)

This feature also appeared in National Geographic Traveller India

For latest travel news and updates, food and drink journeys, restaurant features, and more, like us on Facebook or follow us on Instagram. Read more on Travel and Food Network

Trending on TFN

The 23 Best Places To Go In 2023

Explore Utah’s Mighty 5® and What Lies in Between

Five Epic U.S. National Parks To Visit This Year

Pooja Naik is a Mumbai-based journalist with a penchant for food, art, and adventure. Her affinity for travel has often led her to many cultural crossroads, whereby she savoured butter tea with the resident monks at Thiksey Monastery in Ladakh and guzzled an indigenous produce of green ant gin at a local’s behest in Australia. Her work has appeared in National Geographic Traveller Ind