The main demarcation between milk and dark chocolates is the concentration of cocoa in each of them. Fifty per cent and higher concentrations of cocoa classify as dark chocolate, while anything below this mark is considered milk chocolate. Photo by: GoncharukMaks / Shutterstock

Funky Chocolate Club in Interlaken offers fun insight into the origin of chocolate, while allowing visitors to dabble in the production process.

“Cocoa pods are considered fruits,” Dorota Kravčáková’s words fall like music to my ears. Part-time model and full-time chocolatier, the 28-year-old who lovingly goes by Dori, is helming a traditional Swiss chocolate-making workshop at Funky Chocolate Club in Interlaken, a resort town in Switzerland. She holds up the pods—yellowish-orange and creased, sourced from Madagascar—before placing them on the steel table for my group of eager volunteers to inspect. She then brings out a cracked opened one, which reveals dark brown beans inside; the deep colour indicates its maturity. We pass it around the circle, carefully examining its leathery texture and learn about its medicine-rich properties. The only diversion overriding our visual senses is the heady perfume of chocolate that permeates the room. I feel like I just stepped into Tim Burton’s fantastical realm.

In this chocolate factory, however, it isn’t Willy Wonka but Tatiana and Vladimir—two chocolate connoisseurs and the brains behind the 2014-established Funky Chocolate Club—who run the circus. At their behest, Dori followed her heart from Slovakia to Switzerland and joined the team in 2017, after completing a three month course at the Chocolate Academy in Zurich. On an average, around 7,000 people signed up for the workshop every year until the pandemic came knocking. While the number of participants has since waned, the experience remains a sweet dose of fun.

The place may not feature chocolate rivers, gum drop trees or rock candy mountains, but it certainly lives up to its quirky name. The shop at the entrance arrests my attention. Stacks of pop-coloured beer cans and quirky quotes that scream “beer is cheaper than therapy” line the walls. The adjoining café displays a liquid chocolate churning pot and assortments of fair-trade and organic chocolates that include vegan, dairy, nut and gluten-free varieties. But the real spectacle unravels in the workshops, behind veiled curtains: right where I win my golden ticket.

Inside, I gear up for a lesson in chocolate making and its history. Dori walks over to a corner wall plastered with Swiss flags, a world map and a poster advertising fresh cocoa pods from Brazil. They are lighter in tint than their ripe counterparts and the insides are filled with a sticky, sweet, white pulp. Once the cocoa pods are ready to be harvested, the farmers take them down from the trees and cut them open. “The first step to make a chocolate is to get rid of the pulp and dry the cocoa beans,” Dori begins. The process, similar to drying rice, takes three days. The colour shifts from white to brown, after which it is ready to be shipped to the country of production.

When the cocoa arrives at its destination, it is roasted on high temperature à la coffee beans, releasing its alluring aroma and flavour. The beans are then ready to be ground for the next 72 hours, resulting in a smooth, velvety texture, and are mixed with other high-quality ingredients to make fine chocolates.

Dori moves over to the world map and quizzes my group, “Where do you think chocolate originated?”

“Ghana.”

“Nope.”

“Madagascar?”

“Nope.”

“Ecuador!”

“It’s Mexico,” she reveals.

“The Aztecs and the Mayans were the first in the world to recognise the value of cocoa beans. It was even used as a currency in olden times,” she adds. Before chocolates were moulded into bars, the community held its liquid form in high regard. The humble recipe demanded that the cocoa beans be crushed and mixed with hot water and spices like cinnamon, chillies and vanilla. A drink so revered was reserved only for Gods and members of the royalty. Upon realising its health benefits, it was made accessible to warriors who guzzled it as an energy booster. “It was their version of Red Bull back in the day,” Dori quips.

Soon, the rest of the world discovered cocoa. Hernán Cortés, a Spanish conquistador best known for conquering the Aztecs and claiming Mexico on behalf of Spain, brought it to the court of Spanish royalty, who later shared it with the French. During colonisation, the French introduced it in Africa. Today, Ghana and Nigeria are some of the biggest global producers of cocoa even though the plant isn’t native to the continent. Other key players include Ecuador, Brazil, Peru, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, the Caribbean, Hawaii in the United States, Kochi in India, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines. These regions lie in close proximity to the tropical belt, making it hospitable for cocoa to thrive under specific weather conditions with ample sunshine and heat.

So, what makes Swiss chocolate so popular? The secret lies in alpine milk.

Chocolate tasting, I learn, is much like wine tasting. It requires you to use all your senses. Begin by inhaling the aroma. Then, listen to the symphony of crackle. The louder the snap, the higher the concentration of cocoa. And, finally, savour the flavours. Over the next 20 minutes, I sample a raw bean and six varieties of chocolates, starting with the most unadulterated, bitter version—a one hundred per cent cocoa chocolate—before biting into more sugar-spiked and milk-whisked variants.

Fifty per cent and higher concentrations of cocoa classify as dark chocolate, while anything below this mark is considered milk chocolate. The former pair well with fruits and are perfect for fondues, while the latter makes a great cup of hot chocolate. Switzerland’s most popular rendition—containing 35 per cent cocoa—has won a Gold Award and is creamy and rich in taste. White chocolate lies on the extreme end of the spectrum, made only from cocoa butter—the by-product of cocoa beans. The fat isn’t ideal for consumption, but is popularly used in skin care products and beauty regiments.

I adjust my apron and red toque in time for the main act. In two bain-marie containers, Dori heats dark and milk chocolate separately at a temperature of 45°C each. The hazel pool thickens like lava. The process is called “tempering,” wherein the chocolate undergoes temperature shifts (heating, cooling, resting) to align the cocoa butter crystals within the chocolate. The easiest example of this is known as “seeding,” when small pieces of unmelted chocolate are added to melted chocolate. Now it’s time to put my newfound knowledge to the test.

I hold out a bowl as she scoops a generous portion of melted milk chocolate. Next, I toss in a handful of solid chocolate chunks from the tasting bowl on the table and work the spatula in swift, clockwise motions, until the pieces dissolve completely into the mixture. I repeat the step with a second serving of melted dark chocolate. The workout builds tension up my right arm. Dori sticks a thermometer inside the bowl to ensure the temperature has cooled off to 30°C.

Once the smooth paste has settled, Dori demonstrates transferring the chocolate into a piping bag, which I volunteer to hold for her. She snips it at the tapering end and squeezes its oozing contents into bar moulds, gently tapping the edges to ensure an even spread. “Wastage of chocolate is considered illegal in Switzerland,” she addresses my group point blank while intentionally spilling some over my hand. “A little accident wouldn’t hurt though,” she grins mischievously. I laugh at the mess.

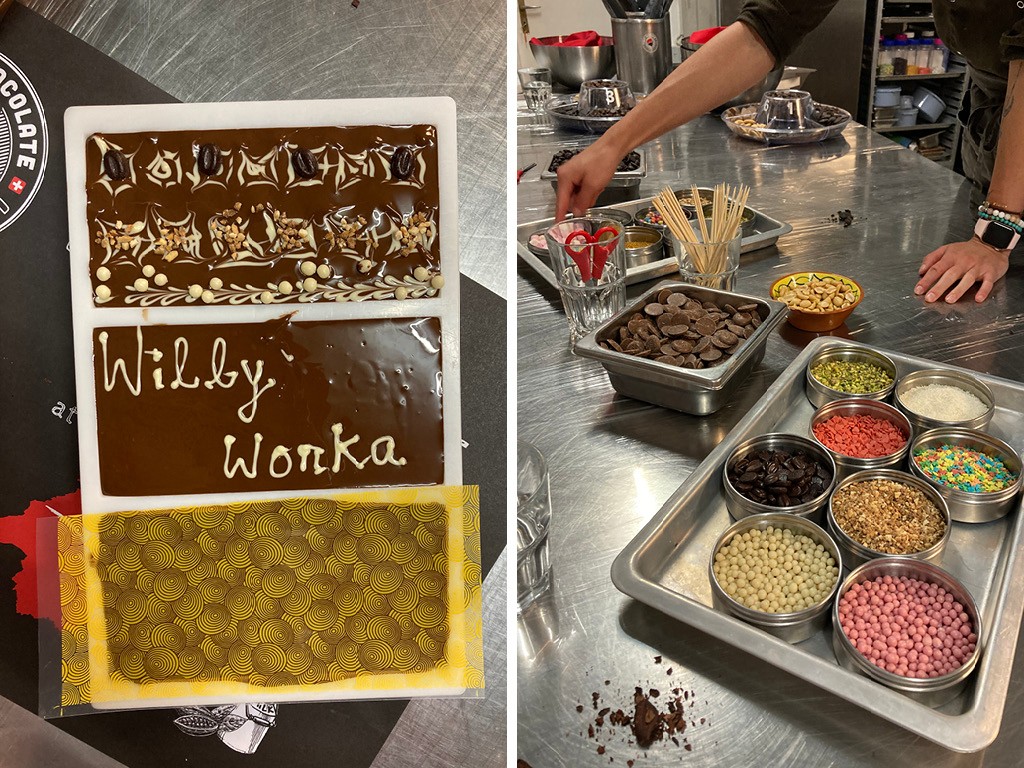

My artistry is put to test when I encrust coffee beans and rice crispies on top of the first bar, delicately paste a geometric edible sticker on the second, and scribble the words “Willy Wonka” on the third. Dori cools the end product in a refrigerator for the next hour.

It is only after I return home to Mumbai a week later that I devour my creation, still neatly wrapped inside a paper bag. It tastes of alpine air and Swiss dreams.

The 75-minute workshop takes place in four batches throughout the day. Tickets from CHF 59/₹4,800 per kid aged 4-14 and CHF 69/₹5,650 per adult. funkychocolateclub.com

DOROTA KRAVČÁKOVÁ’S TOP RECOMMENDATIONS OF SWISS CHOCOLATES

Choba Choba

Chocolate&Love

Milkboy

Taucherli

This feature also appeared in National Geographic Traveller India

For latest travel news and updates, food and drink journeys, restaurant features, and more, like us on Facebook or follow us on Instagram. Read more on Travel and Food Network

Trending on TFN

The 23 Best Places To Go In 2023

Explore Utah’s Mighty 5® and What Lies in Between

Five Epic U.S. National Parks To Visit This Year

Pooja Naik is a Mumbai-based journalist with a penchant for food, art, and adventure. Her affinity for travel has often led her to many cultural crossroads, whereby she savoured butter tea with the resident monks at Thiksey Monastery in Ladakh and guzzled an indigenous produce of green ant gin at a local’s behest in Australia. Her work has appeared in National Geographic Traveller Ind